The Internet of Things: Is it just about GDPR?

by Dr. Davide Borelli, Ningxin Xie and Eing Kai Timothy Neo

The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to those devices and objects that are capable of autonomous data communication with each other, typically for the purposes of gathering information, analysing it and performing an action. Given the current state of chip technology, almost all products can be IoT devices, and Statistica forecasts that there will be 31 billion IoT devices by 2020.

Here are three examples of how data protection issues can arise from the adoption of IoT technologies:

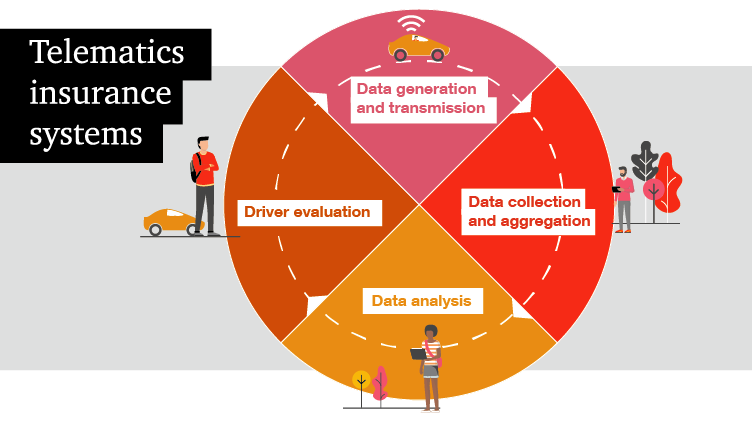

1. Telematics insurance systems

Telematics insurance is a new approach to insurance policies, where a black box, about the size of a smartphone, is installed into the policy holder’s car and collects data on their driving patterns and behaviour. Information is collected on everything from the type of car, speed and distance travelled, down to the times of day and night that the driver tends to be on the road and the way they approach corners and braking.

By collecting and processing this data, the insurance company builds a picture of the driver that is much more comprehensive than the traditional methods of using general statistical evidence relating to drivers. Insurers can then offer their customers tailored premiums that alter quarterly or monthly, based on the communication of data between the black box and the premium calculator. This allows customers to make savings if they are safe drivers and allows the insurance companies to better allocate risks.

However, telematics insurance raises interesting privacy questions. For example, can insurers use data obtained for the purpose of calculating car insurance premiums to inform the terms of other types of insurance? To what extent should insurers disclose data under a portability request if a customer wants to change providers?

2. Smart wearables

Smart wearables provide new solutions to healthcare and ageing issues, medical monitoring, emergency management and safety at work. These electronic devices can monitor, collect and record biometric, location and movement data in real time, as well as communicate this data via wireless or cellular communications.

In fact, wearables are more frequently than before included in corporate wellness programmes. Gartner research estimated that in 2018, 2 million employees with dangerous or physically demanding roles (such as paramedics and firefighters) are required to wear health and fitness tracking devices as a condition of their employment. Tractica research forecasts that more than 75m wearables will be used in the workplace by 2020, as employers recognise that supporting the health of their staff translates into reduced healthcare costs, less sick leave taken, and higher productivity.

Again, smart wearables raise interesting privacy questions: to what extent are the companies who monitor health-related data under an obligation to disclose that data to the subjects they belong to if, for example, they reveal certain negative health conditions? To what extent can companies use this data for secondary purposes?

3. Smart homes and security

‘Smart home’ devices have obvious benefits for both consumers and companies. Their potential profitability is incredible – in 2017 the market for these devices closed at $84 billion, up 16% from $72 billion in 2016, according to a report just released by Strategy Analytics.

Yet, the data protection issues are broad. For example, what is the extent to which the producer of one smart device may be to blame for the failure of another. If, for example, a smart fridge can be hacked and bypassed to unlock a connected smart lock, to what extent should liability for the economic loss of items stolen from the home be distributed between the manufacturers of each product? Depending on how these issues are tackled, there may potentially be significant risk, as a single weakness in the code could potentially be applied to thousands of products written with the same code.

From insurance and healthcare to security products, retail and logistics, it is now clear that IoT can overlap with virtually any industry.

What’s the legislative landscape for IOT?

1. GDPR

Many of the data processing activities involved in the operation of IoT will fall within the material scope of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)1, given that IoT devices tend to process personal data. Consequently, data protection should be built into any IoT solution from the very outset and throughout the development life-cycle, as part of the principle of ‘privacy by design’. Data Protection Impact Assessment may in all likelihood, need to be carried out. Concepts of transparency, fairness, purpose limitation, data minimisation, data accuracy and the ability to deliver on data subject rights should be built into the design of the IoT product. All of this should be documented, and evidenced as part of the GDPR principle of Accountability.

According to a study by the Global Privacy Enforcement Network in 2016, the majority of connected devices fail to adequately explain to customers how their personal data is processed. Such failure is perhaps not surprising given the extent to which IoT services involve significantly more parties than traditional services (for example, sensor manufacturers, hardware manufacturers, IoT operating systems vendors, IoT software vendors, mobile operators, device manufacturers, third party app developers). A key difficulty, in the IoT context, is in determining whether a stakeholder is acting as a Data Controller or Data Processor in a particular processing activity. According to the Working Party 29’s (WP29) opinion on IoT (n. 8/2014):

- Device manufacturers qualify as Controllers for the personal data generated by the device, as they design the operating system or determine overall functionality of the installed software.

- Third party app developers that organise interfaces to allow individuals to access their data stored by the device manufacturer will be considered Controllers.

- Other third parties are Controllers when using IoT devices to collect and process information about individuals. These third parties usually use the data collected through the device for other purposes that are different from the device manufacturer (e.g., an insurance company offers lower fees by processing data collected by a step counter).

- Other stakeholders such as IoT data platforms and social platforms may also be considered as Controllers for the processing activities, for which they determine purposes and means. On the contrary, they may be considered as Processors where they process data on behalf of another IoT stakeholder that acts as a controller.

It's important for IoT stakeholders to conduct an assessment over the processing activities to identify the respective data protection roles (e.g., controller, joint controllers or processor) and correctly allocate responsibilities (particularly in relation to transparency and data breach obligations, as well as data subject rights).

In addition, apps in the IoT may, advertently or inadvertently, directly or indirectly, process 'special categories of personal data'. For example, smart wearables may indirectly collect information that, over a period of time, may be used to deduce the health or well-being of the individual. In this case, further considerations may need to be taken, and explicit consent may be required under Article 9(2) of the GDPR for data collection. It's worth noting that special categories of personal data can also be associated to vulnerable data subjects. For example, developers of connected homes processing health-related personal data may have been specifically designed to process the data of the elderly; in such instances, IoT stakeholders need to put careful thought into providing clear and comprehensive information in a user-friendly way.

2. ePrivacy Regulation

However, the GDPR is not the only relevant legislation for IoT. Another important piece of legislation is the upcoming ePrivacy Regulation2. Despite the fact that the legislative approval process has yet to finish and uncertainty surrounds its implementation date, the position is clear – the ePrivacy Regulation3 will replace the existing ePrivacy Directive and will be directly applicable throughout the EU (and likely beyond).

So, what is the impact of the ePrivacy Regulation on IoT? An examination of the different drafts of the ePrivacy Regulation shows that there's a very real possibility that it will have, in some ways, a wider material scope than the GDPR. Article 4(3)(aa) of the Parliament version of the proposal explicitly provides that 'machine-to-machine communications' are covered by the Regulation. As a result, the communication of non-personal data between machines may be covered by the finalised ePrivacy Regulation but not by the GDPR. For example, end-users’ consent may still be required for processing (non-personal) communication data (Article 8 of the draft ePrivacy Regulation).

However, it's important to note the caveat to this, set out in Recital 12 of the Council version of the proposal, which clarifies that the material scope is limited to transmission services and excludes the application layer (e.g., a mobile app). Therefore, as the application layer does not represent an electronic communications service, it would not fall within the scope of the proposed ePrivacy Regulation, but rather the GDPR (insofar as it contains personal data).

Conclusion

Complying with the legal requirements relating to data privacy will, of course, be of paramount importance for any responsible player in the IoT eco-system. Organisations in this space must be able to evidence - to regulators, consumers, partners and litigants - that they have fully embedded data privacy considerations into their technology.

However, in addition to considering the legal compliance requirements, it's important to lift the conversation to a broader perspective; IoT can bring so many incredibly valuable benefits to society, to industry and to individuals. It also creates privacy risks, particularly in relation to individual dignity and autonomy. The point is that not everything that's legally compliant and technically feasible is morally sustainable, as argued by the European Data Protection Supervisor, Giovanni Buttarelli, at the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners 2018. It therefore becomes a question of data ethics; this requires organisations to have a more fundamental conversation; what's the core purpose/objective we're hoping to achieve with IoT and how does that balance against risks to individuals? What's the right approach for us to take? This is a broad sweeping, high-level conversation that ought not be held solely amongst Data Privacy Officers or data privacy lawyers, but rather with technologists, data scientists, product and risk teams. It's about recalibrating the conversation from one of pure legislative compliance, to a core question as to ethical use of data.

Notes:

1) Regulation (EU) 679/2016

2) Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the respect for private life and the protection of personal data in electronic communications and repealing Directive 2002/58/EC (Regulation on Privacy and Electronic Communications)

3) Directive 2002/58/EC